Sir Percy Sillitoe, the man with ten thousand secrets, deals with the sensational cases of Fuchs, Pontecorvo, Burgess & Maclean

ONE of Britain's great war-time secrets was the "firm'', registered as Tube Alloys. In reality it was the clearing house for atom-bomb research.

Head of the staff was Sir Wallace Akers, of Imperial Chemical Industries, whose job it was to coordinate work on the atom-bomb, including the monthly reports of all the scientists.

One man sent in reports punctually, never pleading that he was too busy. His reports were a model of clear thinking, accuracy and simplicity, despite the abstruse subjects he was exploring. And whenever called upon to explain his reports he showed a flair for reducing them to simple: easily understandable language.

This man was Dr. Klaus Fuchs, among the youngest of the scientists who had come to the forefront in the vital work of separating uranium isotopes.

By 1942 he was recognised throughout Britain and America as a man who excelled at solving intricate problems, and whose results could be utterly depended upon.

It became essential to introduce Fuchs to most secret matters, so that his work would not be wasted. No alien could be permitted to see the relevant papers so it became necessary for him to be naturalised.

On August 7, 1942, Fuchs took the oath of allegiance to the Crown and became British by naturalisation.

Sold Information

At this time he was already, passing information to the Russians, in the belief that they, being enemies of his bitter foes, the nazis, were also entitled to such information.

He had made contact with Simon Kremer, then secretary to the Soviet Military Attache in London, although Fuchs knew only his code name, "Alexander", and he belonged to the Russian Intelligence Service.

By this time Hitler had attacked Russia, and Fuchs began to give the Russians carbon copies of reports he had typed, or the original pencil manuscripts from which the typescripts were made.

At first, he gave them only the results of his own brainwork. But soon he was giving them all the information he could get.

He used to meet a woman agent of the Russian Intelligence Service in Banbury, and continued to do so until he went to the United States for the final, fateful chapter of the work upon the A-bomb.

I think it only fair to the Security services of the United States to make it clear that when Fuchs landed in New York and went to Washington with the other members oi the British mission, he was not subjected to any further investigation bv the Americans, but was accepted as a fully accredited and trustworthy person. He was required only to sign the formal Security undertaking with the United States Government.

But by 1949 we were aware that there was a traitor in our citadel of atomic research. From the inquiries we made it was soon established that the traitor must be the man who was then head of the Theoretical Physics Division at Harwell Research Station—Dr. Klaus Fuchs.

Now, as so often happens in counter-espionage, we had identified our man, but were not able to prove anything against him. Intelligence information is one thing; legal evidence sufficient to justify prosecution is another.

Hated Nazis

The only procedure in such cases is to acquire knowledge about the man himself, for if we know his motives and his state of mind we may then be able to extract from him by skilled interrogation the evidence we need.

Fuchs was not a spy of the storybook variety, any more than Nunn May had been. They were both ideological traitors—psychological and political phenomena of the Twentieth Century.

Few countries enjoyed such good fortune as the Russians in their espionage, for such men as Fuchs, who already had their contacts, were apparently prepared to come forward and seek out the Russians to give information to them.

Fuchs' first foe had been nazism, and in those days the Russians were the opponents of nazism, though they found it easy enough to embrace the friendship of Hitler when it suited them. But men like Fuchs could not make such chamelon-like changes.

Loyalty Ties

However, while he was acting as a willing and eager spy for Russia and facing considerable danger on their behalf he was becoming increasingly aware of the democratic way of life. He made friends in England and began to acquire loyalties to them, and through them he developed a loyalty to Britain.

After the first atom-bomb explosion there was nothing to stop Fuchs from escaping to Russia—except his own decision to stay with us, the people of his adoption, because he preferred to do so even though he risked exposure as a spy.

The communists had taken from him all that he could give, but they had given him nothing in return except £100 that he did not want.

They gave him neither friendship, affection, nor hope for the future, but in England he found all these things, and in America, too, he found them.

Unnecessary investigations could make innocent lives a nightmare

Fuchs, when he lived among the men and women of the democratic world, was completely won over by them. It was too late to save the secret of the atom-bomb, but because he was already in so deeply with the enemy I think we can claim that the ultimate victory was for this reason all the more important and significant.

When we began to study Fuchs' personality in 1949 it became apparent that he was undergoing a deep crisis of conscience, and that if he were approached with an appeal to that conscience there was some hope of being able to complete this process of conversion.

It was with this hope in mind that William Skardon carried out his interrogation on behalf of MI5; it was carried out patiently and with considerable understanding of Fuchs' state of mind.

It became essential to introduce Fuchs to the most secret matters this method was ultimately successful, and, secondly, that at no time was any resort made to the methods of interrogation that are notoriously used behind the Iron Curtain, provided the most interesting and hopeful aspect of the Fuchs' case.

It proved that the weapons of the free world—freedom and truth—are effective ones today. Simply by living among us and observing our way of life and assessing our democratic values, Fuchs became converted, and willingly and deliberately stepped down from his pedestal as the man who held the key to world power.

He exchanged this position for that of a prisoner in a British prison, because his conscience told him that this grim course was the better and the nobler one to take.

One result of the eventual arrest of Fuchs was that the American Federal Bureau of Investigation was anxious to obtain from him any information which might be of assistance to them.

Mr. Edgar J. Hoover sent over to this country two of his senior agents with the request that they should interview Fuchs.

Now, of course, in this country no British subject can be interrogated before his trial, and I had to explain this. The interview could, nevertheless, be permitted after the trial, if Fuchs agreed.

Fuchs was then entirely cooperative in giving the FBI information, and this led to the arrest of American citizens also engaged in espionage.

MI5 came in for a certain amount of criticism in connection with the Fuchs case.

It would have been much more laudable had the department been able to establish—or even merely to suspect—in 1942 instead of in 1949, that Fuchs was passing information to the Russians.

But I have sometimes felt that many people, not knowing accurately the methods of MI5, have come to expect that its representatives must be endowed with a sixth sense.

Given that we had never had any grounds for suspecting Fuchs, what should we have done? Should we have, all the same, arranged for him to be shadowed night and day?

In that case we should have had logically to follow the same procedure in the case of all the other apparently quite innocent men who were engaged on secret work—and their number was fairly large.

It would have been necessary to employ whole battalions of men for the job.

Then you would have a violent outcry, for these men, 99 % at least of whom would be entirely blameless, would, reasonably, protest.

Their lives would have become a nightmare once they realised that their every action was being spied upon.

Diplomats disappear

Moreover, if the police were constantly making arrests because in the general atmosphere of suspicion they became convinced that a scientist handing over, say, a parcel of laundry was probably communicating with a foreign Power, wrongful and probably outrageously unwarranted arrests would be made.

I think that anyone who seriously considers what he is really advocating when he criticises MI5 "inefficiency" in such respects will see that he is advocating more than be intended.

There was wide public concern about the disappearance of the Foreign Office officials, Burgess and Maclean.

Incidentally, I feel that some of the criticisms concerning MI5 action in the case of Mrs. Maclean were quite 'unjustifiable.

She had done nothing to warrant being kept under observation, and no one had any right to prevent her from leaving the country or from going to any place outside it she might choose. And had she been prevented from so doing, what would have been gained?

In so far as the disappearance of the two Foreign Office officials themselves was concerned, I can only emphasise that no shred of legal evidence has ever been available against either of them which could have served as grounds for the issuing of a warrant for their arrest.

There was also manifest great dissatisfaction when Bruno Pontecorvo, another scientist who had previously been working at Harwell, failed to return to this country after a holiday in Italy. The public concluded that he had gone to Russia.

Assuming that this be so, what could MI5 have done in the matter?

"He should have been stopped from going to Russia," was the cry.

But in this country a man cannot be arrested unless there is legal evidence to warrant it.

It is vitally important that we should all bear in mind that if we cry out against the people who have abused their liberty in this country, we must remember that had we deprived them of that liberty without legal evidence against them we should have been taking steps which would, inevitably, have threatened the liberty of every one of us in Britain.

We should, in fact, have been standing at the top of the slippery slope which leads to the setting up of a Police State—in which the ordinary citizen goes in constant, helpless fear of a Secret Poliae against whose decrees he has no redress.

Surely, none of us wants that? I myself, would rather see two or three traitors slip through the net of the Security Service than be a party to the taking of measures which would result in such a regime.

Krupps find victory in Peace

By PETER NICHOLAS.

The firm has huge orders for bridges, steel mills, dams—but they haven't forgotten how to make armaments.

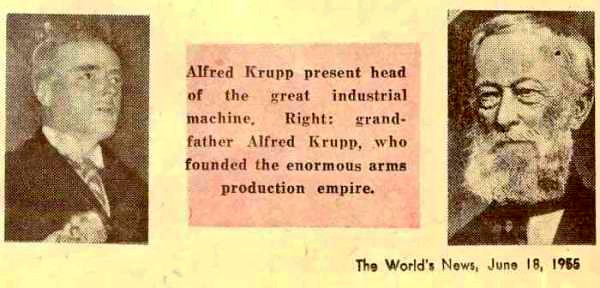

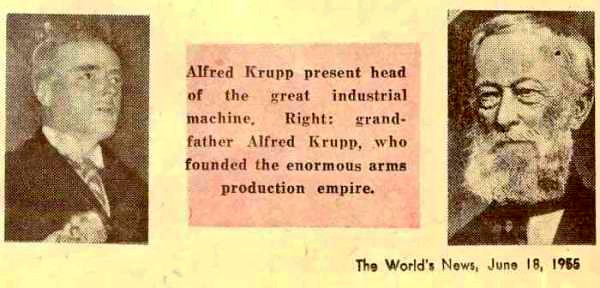

IT is only ten years since Germany was in ruins and the victorious Allies, hastening to hand out justice, decided that the greatest dynasty of death Europe has ever seen—the Krupps armament empire— should be broken for all time.

It has taken only ten years for the empire to gather its shattered resources, heal its wounds and begin growing again. And it is growing even faster on the fat profits of peace and the immense opportunities for industry in the teeming nations of Asia and the Middle East than it ever did in the days of war.

In 1945, Alfred Krupp was arrested as a war criminal. The £200-million Krupp empire was divided into three parts for dismantling and conversion to peacetime maufacture. The Krupp coal mines were carved off the mighty armament organisation, so were the steel and iron works. Huge armament works were dismantled.

Alfred Krupp, the dark, lean emperor of the Krupps gun empire, was locked up in a castle at Landsberg, the place where Hitler wrote Mein Kampf. But, in 1951, when he had served only half his term, he was freed. Krupps were paid £30-million compensation, plus £1-million a year royalties to make up for the loss of their armament plant.

It was a nice start on the road back and the Krupps organisation has never been slow to make the most of an opportunity. Work, strenuous, unremitting work, from the laborers I saw ripping out old machinery at an Essen factory in 1952 to the cold, efficient planning of the Krupps top executives has wrought a near-miracle of recovery.

Now the Allies, particularly Britain, are worried because new Krupps factories produce railway engines, ships, bridge-building gear and heavy industrial machinery at lower prices than anyone else in the world. Locomotives for South Africa, blast furances for India, industrial plants for Greece, steel mills in Pakistan, an engineering workshop in Brazil, dams and power plants in Egypt— all these and dozens of other huge contracts have gone to the re-built and revitalised Krupps organisation.

Immense Output

The big stuff is not all. Krupps factories are pouring out precision machines, tools, household gadgets, trucks, cranes and even false teeth to every market in the world. Their rapidly increasing sales are hitting British manufacturers where it hurts most—in the bank balance.

And now that Germany is a sovereign State again and allowed to make her own arms—up to a certain level—it is expected that Krupps factories will be turning out weapons to help the Western World defend itself against the armed might of communism.

Latest reports from Germany, however, claim that Krupps are not anxious to turn back from ploughshares to swords again. They are making too much money peacefully to be tempted by armaments orders.

Germany has to provide 500,000 men for the NATO joint army in Europe, but Krupps want no part of the juicy orders for tanks and guns and shells that are waiting to be filled.

It may be so—at the moment. But the history of Krupps shows all its financial might and power were built on guns. And the Krupps family has always maintained that it preferred peaceful production to arms. But it was gun production which founded the Krupps empire, the network of industrial power which began in 1812, three years before the battle of Waterloo.

Friedrich Krupp, the first of the family to see the advantages that lie in steel production, claimed he was the only man in the world who had the secret of making cast steel. By 1836 the firm was almost bankrupt, but Friedrich's son, Alfred, took over the reins and made Krupps into a colossus.

It was Alfred (the present Alfred's grandfather) who turned from railway lines to cast steel guns, and, despite ridicule from the Old Guard, who knew bronze was the only stuff you make guns from, Alfred persevered.

The Egyptians gave him his first order. The Krupps have always been democratic—they'll take money from anyone. And as soon as other Powers had Krupps guns, the Prussians began ordering them. By 1864, with a staff that had mushroomed to 6000 in 1864 from a mere 2000 in 1861, Krupps were making guns only for Germany.

In 1870 Krupps guns shelled Paris and if Krupp had had his way, they would have lobbed 1000 lb mortar shells into the French capital as well.

But Prussian red tape is just as thick and tangled as red tape anywhere and when World War I began, Krupps were selling better guns to Brazil than the dumbkopes in Berlin would permit the firm to make for their own country.

In 1887 old Alfred Krupp died, and his son Friedrich took over. The firm prospered and grew, and in 1902 the Prussian aristocrat, Gustav von Bohlen und Halbach, who had married into the family, became the boss.

According to a recently imblished Krupp family history, written by the firm's historian Gert von Klass, Gustav was most unhappy about filling orders for armaments.

The outbreak of World War I was a terrible surprise to Krupp, claims Klass. But it was Krupps shipyards at Kiel which built the first submarine, although the German Admiralty "showed only moderate interest".

When Hitler appeared on the scene, Gustav, it appears, hated him. He hated him so much that the firm chipped in only £12-million to help nazi finances along. By 1945, with Gustav a hopeless drug-crazed invalid, his son Alfred was in charge and had to take the rap for heading the biggest armament set-up in the Reich.

There was great indignation in Germany when poor Alfred was imprisoned, but it was not as great as the indignation in Britain when he was freed in 1951, with only half his imprisonment served.

"If you got killed in the 1914-18 war, it was more than likely by the technical courtesy of a talented old industrial gentleman named Krupp," wrote Cassandra in the London Daily Mirror to his 4-million readers.

"If you got a packet in the 1939-45 war, the chances were that your house, the shell which set fire to your plane and the mine that made you a non-hiker for ever were all made for profit by old Mr. Krupp's favorite son Alfred."

It was the American High Commissioner in Germany, John McCloy, who freed Alfred and let him take his place again at the head of the once great empire his ancestors had built on blood and steel. Alfred went back to the family home, the massive, brooding Villa Heugel outside Essen and was welcomed by his mother, Bertha Krupp—the girl who had a gun—Big Bertha—named specially for her in World War I.

Only six months ago, Big Bertha Krupp, now 71, held a celebration party at the Villa Heugel. Although it was Alfred who went to jail and Alfred who nominally directs Krupps, it is Bertha who decides policy and picks the men who will make the empire run smoothly.

Head of boom

Last year Germany's steel production hit a post-war record of 1,614,849 tons and exports were a record, too—£2500-million. At the head of Germany's industrial boom is Krupps.

Bertha decided the Argentine would be the next place to establish an overseas Ruhr and announced that Otto Skorzney (a nazi commando hero who snatched Mussolini out of Allied hands for Hitler) had been chatting to Argentina dictator Peron about setting up a steel works at San Nicolas, north of Buenos Aires.

The Villa Heugel, with its 800 rooms and 400 servants and £25-million worth of gold plate and art treasures, was ablaze with light and laughter as the guests talked of German prosperity and the shape of things to come.

Germany is prohibited from making chemical or atomic weapons, and may make guided missiles, military aircraft and ships only with an Allied permit. But things look good. The parties at the Villa Huegel have been attended in recent months by diplomats and business big shots from all over the world. Ethiopian monarch Haile Selassie and Turkey's premier Abnan Menderes have stayed with Bertha lately.

The results of these visits are never immediate, but the growth of Krupps—dams in Egypt, blast furnaces in India and railways in South America—is steady and fast all over the world. Krupps employs 30,000 workers now and, although it is not as good as the 160,000 (including slave labor) of Hitler's day, it is not bad.

World-wide contract

But the payroll in Germany is only part of the story. Wherever Krupps goes in the world there are Krupps technicians and experts, managers and planners to tie the whole vast structure into a rambling unity of power and wealth.

The new steel mills near Calcutta, the proposed steelworks in Argentina, the cement factories, the ships, the bridges in the Middle East and South America—all these are post-war developments that are rapidly piling up Krupps interest toward the prewar total of £200-million. After all, Krupps got £25 million for the coal mines and steel works they had to sell in Germany and the money has to be invested somewhere.

The man who is guiding this enormous expansion now was picked out by Big Bertha. He is Berthold Beitz, 41, who recently paid a highly successful visit to America to talk about rayon, nylon and other artificial fabric production.

Krupps have their many hands full with peaceful orders now, but all over Europe people are saying that it will be merely a matter of time before the old firm is back in its old business of making arms again. The West German economy, already struggling to find the men it needs for peacetime production aided by the Allies, will have to divert some of its labor force to weapon-making when the Allies ask Germany to take on its share of armament-making for NATO troops.

When West Germany has to produce its 500,000 NATO troops the labor market will be completely disorganised. Only manufacturers engaged on essential production will be able to keep their staffs and what is likely to become more essential than armaments—there are plenty of things an army needs besides atomic and chemical weapons and aircraft. Millions of pounds worth of light weapons and transport are needed. Head of the list (unwilling although they claim to be) will be the Krupps organisation.

They do not want to lose the money they are making in peaceful overseas trade. Last year they admitted they made "a small profit on a turnover of £83-million". But Krupps have never lost money by making arms.

It is not likely that the West German Government will force anyone to lose profits by making weapons now. So it looks as though the Krupps family will be back in the arms business again whether they like it or not.

Both America and Britain want Germany to make arms again. America because it wants the NATO armies equipped as speedily as possible; and Britain because it thinks it high time the German manufacturers undertook their share of defence and stopped getting preferential treatment in the export markets of the world. Krupps successes have hit the British manufacturer harder than anyone else.

The Krupps family seem to be back where they were 143 years ago—everyone asking them for guns. For a firm that claims it dislikes the armament business they have done very well.